"We felt newly born:" Afghan women footballers train in Doncaster after fleeing Taliban

and live on Freeview channel 276

Players from the country’s women’s development team have revealed how they faced beatings, death threats, bomb blasts and were scared for their futures after the murderous regime returned to power in the Middle Eastern state.

The young footballers have been welcomed to the UK, with Leeds United owner and chairman, Andrea Radrizzani instrumental in helping them flee Kabul.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNow the women are hoping to relaunch their football careers in the UK and have been training at various locations across Doncaster in recent weeks.

In an interview with The Guardian players have been describing their terrifying journey to the UK to escape the Taliban who regained power in Afghanistan earlier this year.

Afghanistan development team player Fatemah Baratean said: “We were on the pitch training that day. All of a sudden there were explosions and bomb blasts all around, 100 metres from us, smoke, people screaming, mothers running. We didn’t know what was going on.”

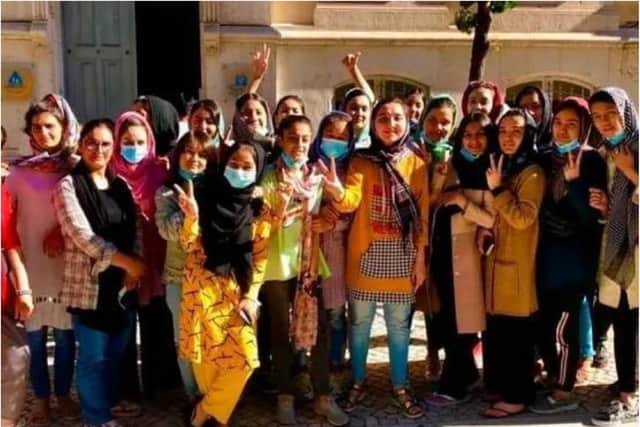

The coach told the team it would be their last session, that the Taliban had seized control and they should take one final selfie together there in Herat before everything changed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We didn’t want to accept that,” Baratean, 20, said. “We were telling the coach it was not true, it was not happening, this was not the reality. But that was our last moment on our pitch.”

Whereas the bulk of the Afghanistan women’s senior national team made it on to some of the last planes to leave Kabul before the Taliban halted evacuation flights, with visas to Australia secured, the development team were stuck and only arrived in the UK on November 18.

“We weren’t prepared,” fellow player Sabreyah Nowrozi, 24, said: “We didn’t estimate that they would suddenly take power. The last 20 years for women and girls in Afghanistan was huge; we had many women actively participating in society – we had doctors, lawyers, judges. A lot of the developments that had happened for women meant we didn’t even think about what would happen if the country collapsed. We didn’t think the country would just give up without a fight.”

“Everything stopped,” added Baratean. “Education, jobs, everything for girls stopped. We were athletes, we were scared for our future. For the first time we saw the Taliban in the streets. It was really frightening.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTalking of the team’s early days, Nowrozi said: “In the first two weeks we started playing outside and we received threats from the Taliban.”

"There was an announcement from the Taliban that if the people that supported us playing continued to support us, if something happened to us, then they would be responsible.

“We didn’t give up, we managed to find a secure and hidden place to continue our game. We moved from being outside on a pitch to a school which was more surrounded.”

“When we would leave the stadium, the men who knew that we were footballers were very insulting – there was a lot of verbal harassment, a lot of insults. We ignored it. We could not fight back because there was a risk they could attack us.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNowrozi’s father was supportive but pressure to stop came from wider family. Her father was labelled “not a real man” and as “having no honour” because he allowed his daughter to play football. Nowrozi was described as a “bad woman”, as having been “westernised” and worse.

“For me it was the same,” said fellow footballer Narges Mayeli. “At first families were against us, they didn’t let us play football, they told us the community wouldn’t accept that you’re a girl and are playing football. People would talk about you, people would argue with you, they would call you names.”

When the Taliban took over, the players headed for Kabul airport after contacting Khalida Popal, one of the founders of the women’s national team who was helping players to get out. It took 20 hours for the team and their families to reach the capital, with a driver relative of one of the players paid to organise transport. He hid their documents and ID cards and they were split into smaller groups.

“We were undercover,” says Nowrozi. “Wearing big burqas, hijabs and masks and loads of clothes to hide our identities. On the way it was so scary to see cars exploding, Taliban checkpoints, many accidents. At every Taliban checkpoint we were stopped and we had to work hard to not be identified.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen they left their homes they felt their chances of getting out were slim and that intensified on arrival outside Kabul airport. “We were being beaten by the Taliban and pushed and forced back, surrounded by gunfire,” says Nowrozi. “But then we had some hope when there was a bus to get us into the airport. We sat in the bus waiting to go, very happy, then there was the explosion [at Abbey Gate which killed more than 180 people] and we had to get off the bus. We lost all hope.

“I was so tired, I had no idea what was next. We were surrounded by family members asking us what was happening. I had no answers. I stood there feeling so helpless.”

Getting out via the airport became impossible as troops sealed the entrances. The development team and their families were forced to bounce from hostel to hostel in the capital, trying to avoid notice while they waited for help from Popal and organisations and individuals who had offered assistance.

“The Taliban had leashes and were beating people,” says Baratean of their experience at the border. “They were forcing women to cover their faces; if their scarf was a little bit down they were beating us with leashes. The weather was so hot and it was hard to breathe among the crowd. They separated men and women. They were splitting us, they were beating us, there was a moment when they saw a letter from the football federation and started screaming at us, asking if we were footballers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We didn’t know what to do, what to answer. We were scared, we said we were and they started screaming: ‘You’re kicked out of our governance, we’ll never accept you, you’re non-Muslims, there’s no space for you in our territories. If you can’t make your way from here you’ll be killed. There’s no way for you to be alive here, we don’t accept you, you have no space in our government.’ We were so scared, we were stuck in the crowd, with a direct threat. We pushed ourselves towards the gate.”

After initially escaping to Pakistan, where they still faced being killed by the Taliban, the UK agreed to host the whole development team with their families - 130 people in total.

“The feeling, especially when we landed and we saw the sign saying: ‘Welcome to the UK,’ was a feeling of freedom,” says Nowrozi. “We felt like we were newly born, that we could breathe for the first time. When we got to the accommodation we felt like we were living the first days of our lives.”

And they have quickly rediscovered their love of football in Doncaster.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It was like a child being separated from its mother for several months and finding them again,” says Nowrozi. “We did not want to be separated from the ball. We were running up and down like crazy on the pitch. Just seeing the pitch and having the ball with us, we didn’t want any distractions. After training they brought food, pizza and water and we were saying: ‘We don’t want it.’ We just wanted to play football, we just wanted to stay on the pitch longer. It is difficult to describe it: the best feeling ever.”

“Someone has to make sacrifices to make change happen and that’s what the women of Afghanistan are doing,” says Nowrozi. “We will do our part outside of Afghanistan to continue fighting with them and supporting them. We did it when we were in our country and we will continue to do it after.”