Music star turned farmer on 'swapping tales of Doncaster youth' with Jeremy Clarkson

and live on Freeview channel 276

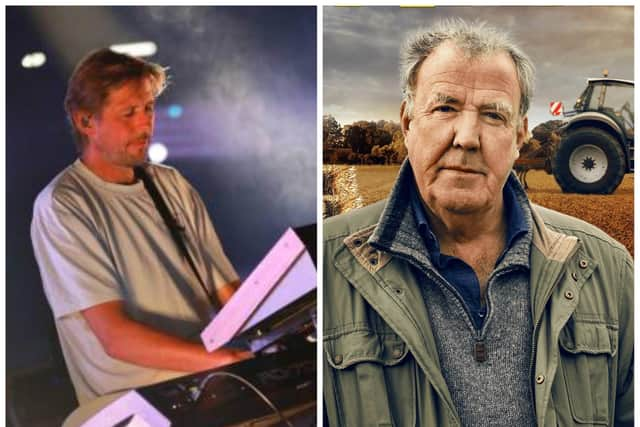

Andy Cato, one half of electronic music duo Groove Armada, who enjoyed hits with chart classics such as At The River and I See You Baby, has spoken of how he’s swapped funk for farming – and how it led to him coming face to face with The Grand Tour and former Top Gear host.

Andy, who performed with the Doncaster Youth Jazz Orchestra before going on to find global success with partner Tom Findlay as Groove Armada, is now a keen farmer, shunning mass production techniques and chemicals for more natural produce.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLiving in rural south-western France, he said: “I decided to have a go at growing my own food.

"Armed with a 1976 Guide To Self-Sufficiency by John Seymour and with the help of our farming neighbours, a corner of the garden was prepared. I built a small greenhouse and, for the first time in my life, planted some seeds.

“From the moment I saw seeds become plants and plants become food, I was hooked. Why wasn't this miraculous process the first thing I had been taught at school?

“This was the start of journey which would leave me convinced that solutions to our health and environmental problems begin with the way we grow food.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“This conviction, and how to make it a mainstream reality, set me on a path from DJ to an unlikely French farmer and baker, and on to becoming a tenant of a National Trust farm, discussing soil health with Jeremy Clarkson.”

After a number of setbacks, he began selling vegetables at the local market – all the time combining it with his musical career,

He said: “I'd head off for DJ gigs with John Seymour's book still tucked in my record bag and amidst the sweat, noise, and lasers, find myself thinking about topsoil — in one teaspoonful of which there are a greater number of living things than there are humans on Earth.

“As my understanding of soil grew, so did a sense of impending crisis. Great civilisations have fallen because they failed to prevent the degradation of the soils on which they depended. A post-war miracle has, for now, saved us from the same fate, but with dramatic, unforeseen consequences.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“These uncomfortable truths combined with my new-found love of growing food led to another pivotal moment: I decided to sell the publishing rights to the songs I had written, a musician's pension, to finance the purchase of a nearby farm in France.

“The first few years were a disaster. I quickly came to appreciate the vast array of skills that were required to be a farmer. I also realised that I didn't have them.

"I wanted to farm without chemicals but didn't have a plan to improve the soil to make that possible'

“Under a tsunami of tractors, grain cleaners, seed drills and other large pieces of complex kit, I was overwhelmed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“When I stopped using the chemicals on which the previous owner had depended, it revealed that the soil was much better at growing weeds than crops.”

“As I struggled to make it work, the farm bills rolled in relentlessly. Farm work began when weekend DJ work often finished — at dawn.

“I was lucky to be able to prop up finances with these gigs but, after a few years I was broke, exhausted and humbled. There seemed no option but to cut our losses and sell the farm. Until a book in a charity shop changed everything again.

“An Agricultural Testament, published in 1940, was written by Albert Howard, an English botanist who travelled to India and collated decades of experiments about agricultural production methods.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Howard was part of a visionary pre-war group of farmers and researchers whose work began the modern organic movement.

“He explained that one of the ways nature maintains its fertility is through a diversity of plants and animals, as we find in undisturbed woodland or grassland, and the opposite of large areas of single crops that dominate the farming landscape.

“I decided to try again. This time, I realised part of the solution involved livestock. With a last roll of the financial dice, we bought some Sussex cattle.

“For a vegetarian of 20 years, who hadn't had a dog or cat, this was a steep learning curve, not helped by the neighbour's untrained collie chasing the cows all night and turning my orderly paddocks into scenes of desolation. The first time I drove a cow to the abattoir was a moment of deep introspection.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I wrestled with machinery and crop combinations that could regenerate and harness natural processes rather than fight against them.

Plants like beans or clover, able to capture nitrogen from the air and store it in the soil, lessening the need for fertiliser. Frost-sensitive plants to keep the weeds down then give way to winter cereals for which frost isn't a problem. Flowering plants to protect crops by attracting beneficial insects, just like marigolds do when planted alongside tomatoes.

“The key is managing these combinations effectively, and there were many more setbacks than breakthroughs.

“But when the breakthroughs came, like the field of rye and oats that was alive with bees feeding on the deep crimson flowers of the clover we'd planted as a companion, they were euphoric. Eventually, we were growing nutritious grains in fields full of life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“But I learned that growing was only one part of the story. When selling grain into the market there is only one measure — weight. Not how nutritious it might be, or the effects on the environment of how it was grown.

“So, to realise the true value of our harvests, we installed a mill and produced flour ourselves.

“But most local bakeries had baguette recipes they weren't keen to change. With flour sales stalling, I had to learn to bake bread. The flavour was great, but it took much longer to learn to make the loaves look passable. Even then, the local stores told me they already had bread suppliers.

“As a last-ditch effort, I began distributing to families who had stopped eating bread because of digestive intolerances. The response was excellent and, from here, word of mouth eventually led to a farm shop, and a bakery team supplying local schools and restaurants.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“As news of our efforts spread, I found myself delivering a loaf to the French president and, on a surreal day in an ornate Palais, becoming a Chevalier de l'Ordre du Merite Agricole. My son asked if I would be given a suit of armour.

“Friends George Lamb and Edd Lees had helped me set up the farm bakery. Now came their pivotal moment, leaving jobs in TV and finance respectively to found Wildfarmed.

“We wanted to build a community of farmers producing crops like we had in France, at scale and financially viable, without every farmer needing to become a baker as I had done.

"We wanted to give shoppers food choices that could positively impact their own health and that of the environment.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Crucially, we wanted Wildfarmed food not just to be the preserve of the wealthy. That is why we called our project The Long Road To Greggs — the day Wildfarmed flour is in a Greggs sausage roll, things are happening at a scale that can make a difference.

“With Britain the place where we had the best chance of this working, I applied for the tenancy of a National Trust farm in Oxfordshire. The award of the lease came after a competitive process; stuck in France thanks to Covid, there were rounds of online interviews that the kids likened to an agricultural reality TV show.

“Dawn, late May the following year, and I was terrified. Machinery issues the previous autumn and difficult weather meant that the fields were not at all how I wanted them to be. However, I was due to welcome some of the UK's best farmers, members of our new Wildfarmed community.

“Last autumn, I was contacted by a potential new Wildfarmer, not far from me in Oxfordshire, concerned about the damage being done to his soil and fed up with the amount of financial risk on his farm relative to the return.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The farmer asked me over for a chat. I was surprised to find cameras rolling the moment I arrived. Jeremy Clarkson and I walked out to look at his fields, swapping tales of our Doncaster youth.

“There are brilliant farmers all over the world, growing abundant harvests of every type of crop, in ways which work with nature rather than fighting against it. It's not easy and there is no magic wand. Our Wildfarmed growers show amazing collective resolve in working through the difficulties of nurturing landscapes back to life.

“But fields, food, and people full of life and health is a path we can take. When U-boats circled the UK in 1939, we completely transformed our food system in just a couple of years. Together, we can do it again.”