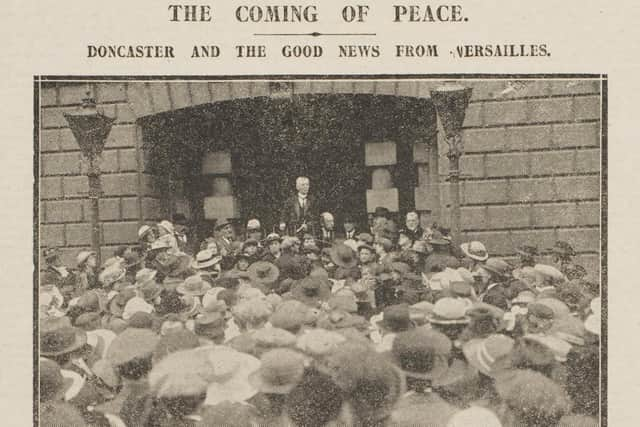

The First World War peace celebrations in Doncaster

After four long years of the First World War, people gathered across the borough to decide how to celebrate Peace.

Local history volunteer Lynda Regan has been scouring the archives to discover what life was like in wartime Doncaster, before the Peace Treaty was finally signed in June 1919. She discovered the forgotten story of Doncaster’s peace ‘negotiations’ hidden amongst newspaper cuttings.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe first sign of trouble in Doncaster emerged in local newspaper reports in February, where the council made a pledge that peace festivities would cost the public nothing, and that there should be no appeal for subscriptions. By April, however, the Corporation’s enthusiasm was waning. As it quickly became apparent that resources were scarce, they backtracked, claiming "every pound saved by the Corporation from needless expenditure on peace jubilations will be a pound available toward the handsome contribution with which the municipality may give a magnificent ‘lead’ in the matter of the permanent War Memorial."

By June 1919, the international Peace Treaty had been agreed, but Doncaster was still unable to agree on any official peace celebration – or even a war memorial. It was described as a “fiasco.” The situation became even more fraught on Tuesday 1 July, when the government announced that there should be a day of national rejoicing on Saturday 19 July. Doncaster’s officials were in a spin – market day would need to be changed; there wasn’t time to illuminate the Mansion House properly; they couldn’t organise catering in time… In the end, they decided to simply scale the event down into a tea party for schoolchildren on Friday 25 July.

For local people, this was the final straw, and the Doncaster Gazette was full of angry letters on 18 July. ‘Disgusted Burgess’ wrote:

“It is now understood that the Corporation… have decided to celebrate the declaration of peace by doing nothing except giving a treat to schoolchildren. If this be correct it will not only be a lasting disgrace to the town but we shall be a laughing stock even to the villages in the neighbourhood. There are now in Doncaster hundreds of returned soldiers. Is nothing to be done to welcome them?”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTensions were rising, however: while some ex-servicemen were unhappy about the lack of official celebrations, other returning servicemen were deeply distressed at their treatment, feeling strongly that money shouldn’t be wasted on celebrations when they were struggling.

It didn’t take much for local anger to erupt into an ‘Attack on the Mansion House’, reported in local newspapers on 17 July 1919. A journalist describes a charity ball in full swing in the Mansion House, while men – including ex-soldiers – stood outside, outraged by what they saw as a “Corporation beanfeast” while the “joy day” celebrations had been cancelled and they were scraping by trying to make ends meet. They attempted to get in and the scene became ugly as the crowd outside grew and feelings ran high. Windows in the Mansion House were smashed and missiles thrown at the police, one of whom, Sgt Gray, suffered a head injury from a piece of lime that went right through his helmet. The crowd also rushed the Mayor’s house and smashed windows there. It took a police baton charge to finally bring things under control.

Mayor Jackson felt that he had been unjustly given the full blame for the failure of the peace celebration plans. He put up posters around the town in which he protested against the events of that night and the “baseless slander and calumny” heaped upon him. He gave a resume of the proceedings in the Peace Celebrations Committee and the Town Council that had led up to the cancellation of the celebrations. He said that personally he would be only too glad to carry out the plans, but that no money had been handed over to him for the purpose and nor could it be without the consent of the Council.

Local communities started organising their own festivities, raising the money themselves. The Workhouse announced there would be tea and sports for all the inmates, while Axeholme and Gainsborough villages decided to club together with joint celebrations. Meanwhile in town, the YMCA stepped in to "provide a programme of events, including sports events and a torchlit procession and fireworks – all sanctioned by the very grateful Mayor!

In the end, Doncaster’s celebrations lasted for a whole month, as local people put their hearts and souls into the festivities.