Retro: Slums where raw sewage ran through the streets

That and perhaps fly-tippers who curse this city.

The door was once the rear entrance to St Jude’s Church School and can be found on Cupola on Moorfields.

Firstly, the name cupola comes from the name of a type of blast furnace that stood at the top of the then un-named street late in the early 18th century.

The shape of the furnace gave Cupola its name.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMoorfields is just a shortened version of Shalesmoor Fields, with Shalesmoor being a corruption of Sherramoor, meaning a boundary from the old English word Scearu meaning divided.

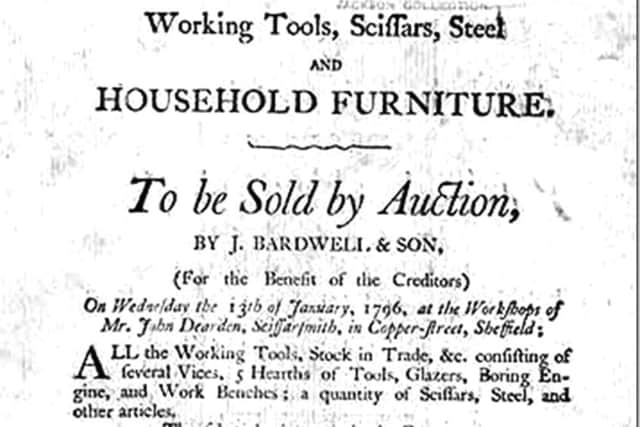

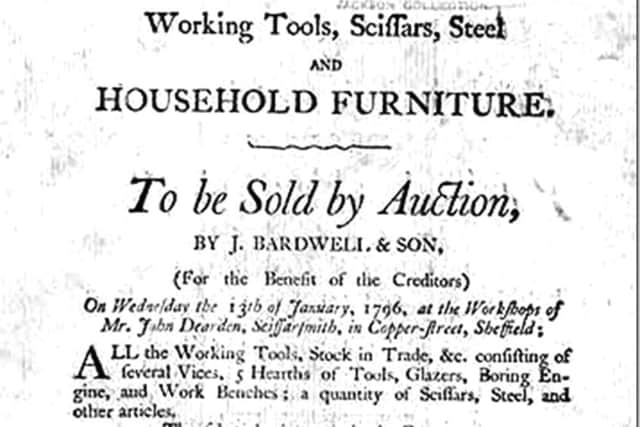

The following are extracts from directories of the time.

“The Moorfields District comprises Gibraltar Street, Shalesmoor, Moorfields, Russell Street, Sheffield Workhouse, Kelham Island and its boundary lines are the River Don, Dunn Street, Matthew Street, Doncaster Street, Smithfield, Furnace Hill, Bower Spring, Cotton Mill Walk, and Union buildings.”

St Jude’s was built near the junction of Cupola and Gibraltar Streets, on an obscure and confined plot of ground given in 1849, when the first stone was laid.

After standing more than a year, on Sunday, November 7, 1852, when roofed and nearly finished, the church fell down, owing to some defect in the foundations of the tower.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo complete was the wreck that the work had again to be done from the foundations, after the necessary funds had been raised.

The present church is on a different plan from the original and was consecrated on June 5, 1855.

It cost about £2,400, and is in the Early English style, surmounted by an octagonal bell turret and having 950 sittings – all free.

The East Window is enriched with stained glass.

John Gaunt of Darnall gave £1,000 towards the two buildings – and £550 was given by the Incorporated Society with £350 by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe church and school were raised to serve one of the many slum parishes in the town.

In 1843, before he began writing A Christmas Carol, Charles Dickens visited the industrialised towns of Manchester and Sheffield.

He was appalled by the conditions in which poor people lived in these slums.

Sheffield had suffered badly during the war with Napoleon because many of the European countries had stopped buying our goods.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt caused terrible poverty. Out of a population of 31,000, there were over 10,000 people in need of help from the parish.

When the European trade started again the population of Sheffield grew rapidly, mainly because of its steel industry.

By 1841 there would be 110,000 people within its boundaries, and hardly any sanitation.

For thousands and thousands of people, there were no toilets and no clean water.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAll household rubbish from these overcrowded dwellings, including excrement, was dumped in the street and flowed through an open sewer.

These living conditions meant that disease was common and people did not live long.

At this time the townsfolk of Sheffield died at an average age of just 27.

This terrible life was mostly ignored by the well-to-do who lived in the more affluent areas of the town.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe standards of working-class housing in the town, like the standards of sanitation, deteriorated in the 1840s and 1850s with the pressure of population, but they were still above those of other industrial towns.

In Sheffield, the local artisans traditionally lived in separate houses and the numbers of persons per house were lower than those of other large towns.

Generally, in Sheffield, the average of the comfort of the lower classes was above that of most other places.

“Sheffield Artisans,” Dr JC Hall wrote in 1857, “have generally a house for themselves, and those in the suburbs frequently also a garden. In good times, it was unusual to find two families under the same roof.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAn examination of the detailed returns of the 1851 census shows however, that many working-class families were obliged to take in lodgers, and even without them the accommodation was intolerably cramped in the case of larger families.

The standard Sheffield workman’s house was built of brick, made cheaply from local clay and covered with local slate.

It had a cellar, a living room on the ground floor, a bedroom and generally an attic or second bedroom on the second floor.

The cellar was not normally inhabited.

The daily activities of the family were concentrated in the living-room, which served as kitchen, scullery, dining-room, living-room, wash-room and bathroom, and on wet days the clothes were hung up in it to dry.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe room was usually paved with flags, its fireplace was fitted with an oven for baking, with a side boiler for hot water, and there was also a dished slop-stone with a lead pipe into the sewer or the street channel.

The cooking was done on worn-down grindstones placed in front of the fire.

In the main bedroom a room with a boarded floor and fireplace, slept husband and wife and the younger children.

The attic at the top was a low room, no more than seven feet high usually with a sloping ceiling with a low window to let in light.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSome had fireplaces and were used by children as a bedroom or by a lodger.

I couldn’t imagine how anyone could live in these conditions.

Today some of the tenants who are given a council property expect everything provided.

Most of my generation waited until we could afford the things that made a home and not getting saddled with debt.